Hearing you have metastatic breast cancer results in difficult sensations and emotions, including shock, fear, disbelief, and numbness. My mind and body felt all of those when the doctor delivered the diagnosis by phone. Shortly after that call, I felt other strong emotions—anger, betrayal, grief, and sadness. I cried in the arms of my husband, who quietly said, “What do we do next? You are a strong person. You have always been a fighter– never backing down from a challenge.” He was right. Giving up and wallowing in despair would just hasten my death.

After the news of diagnosis, my first steps were to select a healthcare provider (oncologist), gather my medical records, and make a clinical appointment. As I read through my records, the medical terms on the pages were like a new foreign language. How would I learn what they meant? What treatments did I need?

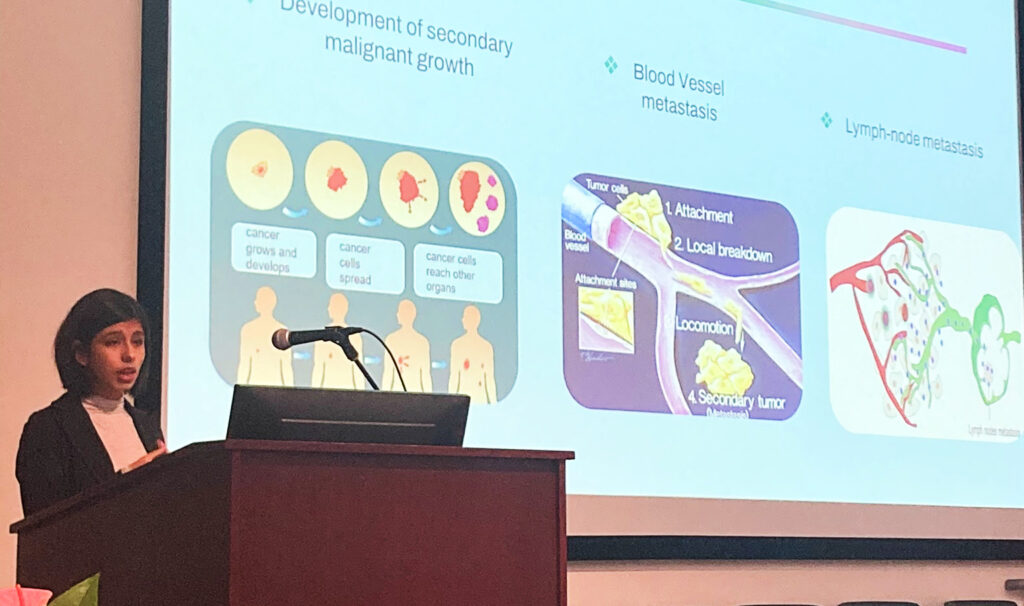

Armed with medical insurance, a crucial necessity to access quality health care, the door was open for me to consult with an oncologist who had experience treating a large number of metastatic breast cancer patients at a cancer research medical center. I soon learned that metastatic breast cancer is not one disease, but a number of subtypes. Each type drives the growth of cancer cells differently and are treated differently. My early stage breast cancer twelve years earlier was fueled by hormones—estrogen and progesterone. But in the metastatic setting, my cancer cells, which traveled throughout my skeleton, spine and liver, had mutated and now were fueled by an overabundance of a protein called HER2 neu. A pathology report uncovered this change and was crucial to my future and in helping the oncologist select the “right” treatments for me. In language I could understand, the oncologist recommended two treatments—a targeted agent for the overabundance of HER2 and an oral chemotherapy pill to attack the metastases that had spread in my body. As I listened to the word “chemotherapy,” I pictured myself with a bald head. I became my own advocate when I asked how I would be negatively affected by these treatments. The medical term is “toxicities.” I was told I would not lose hair with this oral chemotherapy. That was good news.

Because I was employed full time when I received my metastatic diagnosis, I asked about other toxicities like fatigue or diarrhea; how often would I have to come to the clinic; and how long would I be there. Told I had to visit the clinic every three weeks for most of the day, I nervously realized that I could not hide my diagnosis from my employer and work colleagues. What would they think of me? Would I be allowed to keep my position? I also asked my doctor how she would know if the treatments were working. The doctor explained that a number of blood and imaging tests would be used to follow the cancer’s response to treatments.

Finally, the oncologist reminded me that unlike early stage breast cancer, where the goal of treatment is cure, the goal of treatment now was not a cure, but rather, control of the growth of the cancer cells and helping me maintain a good quality of life. That last goal really was important. I wanted to live each day to the fullest. I chose not to ask how long I would live. I didn’t believe one person knew that answer. And, to be honest, I wanted to hang on to hope that my treatments would work.

Two years after my diagnosis, I decided to advocate for more metastatic breast cancer research and improved access to health care. Policy does matter for cancer patients. I also use my knowledge and experiences to inform and educate other patients about the disease and how they can pursue strategies that will help them achieve the best possible outcomes.