It was a perfect spring day. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky on this spectacular April 1st afternoon. My friend Beth insisted on going with me to the surgeon’s office to get the results of my biopsy, even though I was adamant she didn’t need to come. We sat at Wegman’s and shared a chocolate chip cookie that had been half dipped in dark chocolate.

I wasn’t worried about the biopsy. The surgeon had been fairly confident that this was just another calcium deposit. These breast calcifications are common after age 50. I had a couple removed a few years prior. The only thing I was concerned about was that we were leaving for spring break on Saturday and we were frantically waiting for one of my daughters’ passport to be renewed.

As we sat in the waiting room, my husband stood outside the hallway trying to get through to the passport agency. The nurse called me into the examination room. Beth came with me. The nurse stepped out to get my husband, who was annoyed because he had to give up his place in line with the passport agency.

The surgeon finally entered the room after what seemed like eternity. “You have cancer,” he said. When those words are directed at you, everything becomes a blur. I felt like I was having some type of out of body experience. I heard nothing else he said. I only heard my heart pounding and felt my body shaking uncontrollably. I don’t remember much else about that visit. I’m so grateful that my friend Beth had insisted on coming with me and that she had taken copious notes.

As I reflect on my treatment journey, I recall several times when I questioned whether my bad experiences were related to racial or gender bias or something entirely different.

During my next visit, my surgeon recommended a lumpectomy. I opted for a double mastectomy as a more preventative measure. My surgeon said I wouldn’t need chemo or radiation with the mastectomy and could possibly be back at work in a couple of weeks.

I had excellent insurance, a PPO. I had no idea at the time that I would personally have to seek out various specialists for each stage of the process. I found a plastic surgeon who coordinated with the general surgeon and my surgery was set for mid-May. I had a mastectomy and immediate reconstruction. A week later I was told that although the initial tests showed no cancer in my lymph nodes, the later pathology testing showed 2 out of 6 nodes tested showed traces of cancer: I moved from stage IIa to stage IIb. This meant I would need radiation.

I would have been lost had it not been for my friend and neighbor, who was going through her own breast cancer journey for the past year. She told me about what to expect at various stages of the treatment process. She told me about the importance of getting second opinions and advocating for yourself. She had been told in her late 30s that she was too young to have breast cancer. Later when a lump was found, she was assured it was most likely a stage I tumor.

My next step was to see an oncologist. I made an appointment at a cancer care facility near my house. I remember feeling hopeful as I walked into the welcoming waiting room. The sun filtered through the room surrounded with windows and live plants. Soon a nurse took me to the examination room. After taking my vitals, she asked me to wait for the oncologist. I anxiously waited for about 30 minutes.

When the oncologist came in, I found it odd that he didn’t even look at me. Instead, he casually laid a piece of paper down on the table between us. On the paper, I saw my name, my incorrect age, and my cancer diagnosis. He said, “You have stage IIa breast cancer that is ER/PR positive. The standard of care for this type of cancer for someone your age, after undergoing your mastectomy is chemo followed by a month of radiation treatments.” I asked him if the standard of care he just quoted would be the same for someone who was two years younger than it stated on his piece of paper. He said it was.

I felt like he didn’t think of me as a human being. He didn’t see me. He didn’t care to know anything about me. He didn’t care that I ran my own business, that I had a Ph.D., that I had three young daughters, that I was the essential breadwinner for my household, and that I liked playing practical jokes and traveling. On his way out, he told me one of the nurses would come in and explain the chemo treatment and schedule the appointments.

I sat in that room alone: I waited, I waited and I cried. After nearly an hour, I wandered out of the examination room to find out why no one had followed up with me. The woman at the desk, surprised to see me, embarrassingly said, “Oh my God, she forgot you were waiting and went home.” I felt dehumanized: I walked out. I saw a second oncologist. He was more personable but also appeared uninterested in my concerns and questions. I wondered, “Is this the norm for those traveling through their breast cancer journeys?”

I began to search for a third oncologist. This time, I did my homework. I defined the kind of oncologist I wanted. For me, that meant a female doctor, who was still involved in clinical research and was associated with a university. I soon found such a doctor. On my first visit, she asked “What do you know for sure about your next step?” I told her that I knew I would have to have chemo and then radiation. She asked whether anyone had told me about the Oncotype DX genomic test. This test shows the likelihood one would benefit from chemotherapy and provides information about a patient’s chance of recurrence. She said I was the perfect candidate for this test as a woman with early-stage invasive stage IIa breast cancer.

I was stunned and asked “Why didn’t the other two oncologists mention this test?” She paused and said, “Perhaps because it isn’t covered by insurance.” Okay, how much did the Oncotype test cost? How much chemo cost? She told me the Oncotype test cost $3,000 and chemo cost about $70,000, but would be covered by insurance.

Why didn’t the other two oncologists tell me about this test? Was it because they didn’t know about it? Was it because they did not want to take the time to tell me about it? Was it because they assumed that because of my skin color that I couldn’t possibly afford a $3,000 out-of-pocket expense? I don’t know. I’m happy to report that I did get the Oncotype test, which showed I didn’t need chemo treatments. My adjunctive therapy would consist of radiation and hormonal therapy.

I started radiation treatments. It was tough, but I pushed through. A few months after my radiation treatments ended, I developed excruciating neck pains and headaches. The radiologist wasn’t sure why this was happening and sent me to my oncologist. My oncologist referred me to various specialists. Weeks turned into months, and months turned into a year. My constant pain was almost unbearable.

The only solution offered by various specialists was to take opioids for pain. I refused. I told them my research work was detailed and involved a lot of statistical analysis, so I couldn’t afford to be drowsy. I always asked each provider I saw why I was having these pains, and they could never provide an answer. They didn’t appear interested in determining the reason for the pain.

I believe that our healthcare system is structured in a way that doesn’t reward detective providers. It is set up for providers to quickly find a “pain point,” prescribe a treatment, and then assembly line that patient right out the door. I probably saw a dozen specialists during this period. I remember one saying after I asked why I was having this pain, “Look, you should be grateful. You don’t have cancer anymore.” His words were like a slap in the face. Why would he say that to me? Was it explicit or implicit bias due to my race or gender or was he just insensitive or a jerk? I don’t really know. But I knew I didn’t want others to suffer through these kinds of negative experiences.

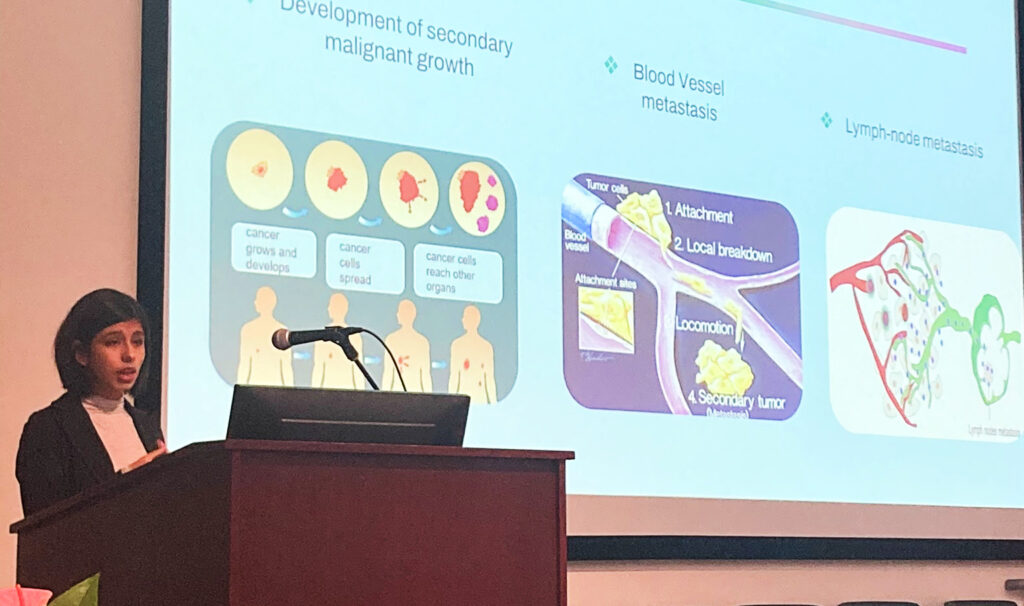

I was but one voice, but I knew I needed to use it to amplify the voices of breast cancer patients and their families. The first thing I did was study: I needed to become a more informed consumer so that I could become a better healthcare advocate. I read about the various types of breast cancer, treatment options, adjuvant therapies, breast cancer medical terminology, how clinical trials worked, and the importance of scientific evidenced-based research studies. Next, I volunteered to serve as a consumer grant reviewer on a Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program for breast cancer research. I wrote a presentation for the American Cancer Society and patients entitled “The little and not so little things that do matter to breast cancer patients.” I helped newly diagnosed patients navigate through the system.

As an opinion research specialist, I turned my businesses’ focus on helping patients effectively advocate for their care, to help patients make sure their providers listened to their concerns, to help patients understand their treatment and their treatment options. I’m proud to have interviewed patients to provide content for a couple of patient focused educational websites: SickleCellSpeaks.com is for patients with sickle cell disease (which largely affects people of color) and the other was for patients with tardive dyskinesia (a life-altering nervous system side-effect of some psychiatric drugs). These sites not only answer clinical questions about these disease states, but also address the explicit and implicit bias these patients often face because of how others view our characteristics (i.e., race, sex, age, or mental and physical disabilities).

All of us have some implicit biases. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity says, “implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner.” An interesting and eye-opening tool you can use to help understand your own biases is the online Implicit Association Test (IAT) offered free by Harvard University .

To my breast cancer sisters, I say speak up! Tell your provider if you need them to clarify something you don’t understand. Tell them if something they say appears insensitive or biased. Help them see you as a human being with dreams, lives, friends and family and not just a breast cancer title.

My name is Rosita. It’s not female, age 52, stage IIb, ER/PR Positive!