GMU, With Ties to Italy, Aims to Be a Biotech Force

By Michael Laris

Wednesday, February 27, 2008; B01

The tiny pieces of tumor, cut from 51 Italian cancer patients, arrived at a suburban Washington laboratory in boxes packed with dry ice.

Doctors at the University of Padua had frozen 51 nubs of tissue taken during colon cancer surgeries and another 51 slices from the patients’ livers, where the disease had spread.

A courier then transported the 102 tubes to a white brick building in a half-built technology park 4,300 miles away in Prince William County, where researchers from George Mason University began tearing through the cells to learn how cancer grows and travels in the body. Discoveries from the Italian tumors are being used to develop a clinical trial for patients at Inova Fairfax Hospital.

For Virginia officials, who have spent $5 million luring talent from Bethesda’s National Institutes of Health and paying for the work, the goal also is to make the region west of the Potomac River a national biotech player.

The effort is part of an aggressive strategy by two former U.S. government researchers, a group of Fairfax County doctors, and state and university officials, who have quietly pieced together a network they hope will allow them to leapfrog the bureaucracies of better-known research institutions to speed discoveries and get personalized treatment to patients quickly.

“The blank slate we were given didn’t exist anywhere else,” said Lance Liotta, former chief of pathology at the National Cancer Institute, who along with Emanuel Petricoin, a former senior researcher at the Food and Drug Administration, and an eight-person research group was recruited to George Mason in 2005.

Their approach has been to build tools and relationships to understand what drives disease, concentrating on early cancer detection and late-stage treatment, but also touching on everything from schizophrenia to the search for human growth hormone in the urine of baseball players.

Their partners have given them access to the human tissue and serum crucial to their research. Advances are channeled back to patients here and in Italy.

“Cancer is a global problem,” said Claudio Belluco, a partner and surgeon at the National Cancer Institute in Aviano, Italy. “You have to fight it with the most advanced technology, facilities and brains you have in the world.”

Liotta and Petricoin speak about their work with the glee of puzzle solvers and the gravity of those facing down diseases that kill millions.

“Lance and I are hellbent. Nothing is going to stop us,” Petricoin said. “We’re going to do whatever we have to do to realize not just our vision but the growing vision of personalized therapy.”

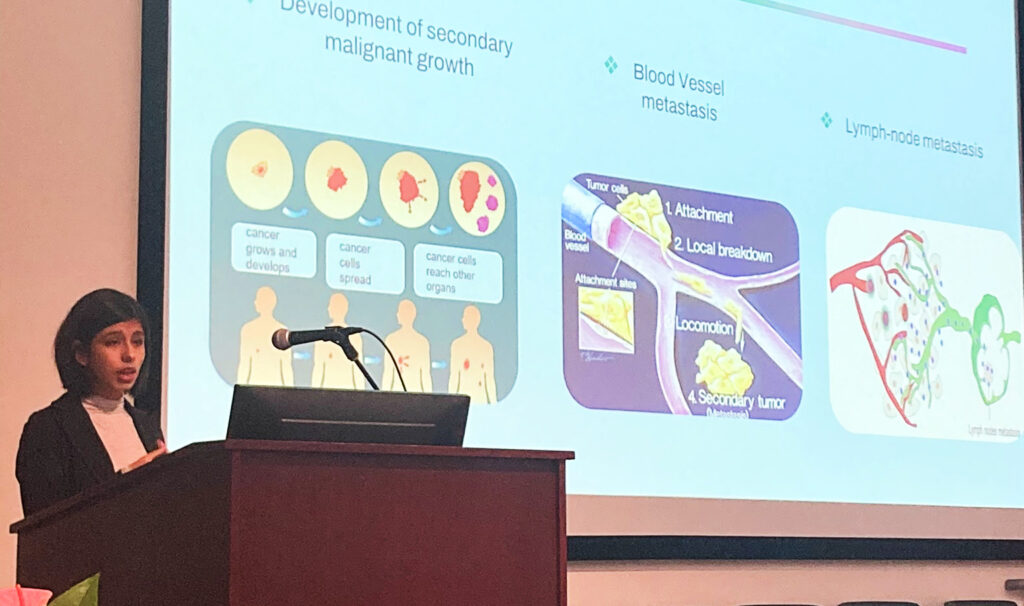

They start with the central premise that each person’s cancer is different. That’s because the proteins that do the work of a cell, which grow out of control in a cancer, follow different paths to reach their destinations.

“It’s like a GPS thing on your car, a highlighted route. It drives a patient’s cancer,” Liotta said.

Researchers around the globe are searching for spots along those routes that, if blocked with the right drugs, would thwart the growth of cancer cells. The emerging field is called proteomics.

On a recent afternoon in their lab at GMU’s Prince William campus outside Manassas, Petricoin reached for a rainbow-colored biochemical chip that is central to their work. Researchers blow apart cancer cells using detergents, then apply what’s left.

Then they feed the chip, dotted with cancer from many patients, into a machine they developed to look for a map of how the proteins wreak their destruction. They founded Theranostics Health to commercialize the technique.

Their insight in finding highlighted routes captured Belluco’s imagination in 2001.

A decade earlier, Belluco had established a tissue bank at the University of Padua, where Galileo once performed secret autopsies.

“I was storing frozen tissue from every patient who underwent surgery for cancer,” said Belluco, known in Padua as a “volcano,” a source of intense and contagious enthusiasm. Petricoin, meanwhile, joked that he and Liotta were sometimes seen as “a double-headed monster” because of their determined personalities.

It was a good match. Soon the Italians were creating a national serum bank to be used for research on both sides of the Atlantic.

Liotta and Petricoin eventually bristled under the limits of working for the federal government. In 2004, they were called to testify before Congress over a consulting arrangement that had been approved by NIH supervisors.

They left for GMU the following year. They said they wanted the freedom to cut through the practical problems that prevent discoveries from reaching patients, such as by finding new ways to collect cancer samples and building relationships with the doctors and firms that can spread advances.

Once a breakthrough is published, “99 percent of the work is still to be done on that discovery for a patient to benefit,” Liotta said.

They have partnered, for example, on a trial in which George Mason researchers are on hand for the biopsies of patients with multiple myeloma, a kind of bone marrow cancer. Greg Orloff and his colleagues at Inova Fairfax take a sample of living cancer cells and, within minutes, the GMU researchers treat the cells in a dish with dozens of possible drugs. Researchers analyze the cells to see whether any of the drugs worked, information doctors can use for treatment.

The partnership with Italian experts provides young talent and what amounts to a human database.

About 500 samples of serum, the protein-rich liquid that separates from clotted blood, have been flown to George Mason from cancer centers in Italy, along with 250 tissue samples and a cadre of Italian researchers, some of whom have been a bit mystified by their new campus and suburban life.

“It was like, George what? I never heard about that,” said Alessandra Luchini, who came from north of Venice and was awed by U.S. geography. “You can survive in Italy without a car, without Internet,” said Luchini, who lives in Burke.

But she was at ease with the bubbling cylinders she used to develop a new class of nanoparticles that are among the lab’s most promising inventions. They act like tiny lobster traps. “You can put inside this particle the bait you want. We are developing new baits every day,” Luchini said.

When the particles are dumped into serum, they search out and collect tiny bits of floating cancer, giving researchers a way to test patients before tumors can be found.

“That’s many billions of them,” Liotta said, pointing to a tube of blue liquid in the lab. Each particle, made of a meshwork of polymer strands, is one-fiftieth the size of a red blood cell. “It’s fun, isn’t it?”

They’ve also made progress on other baits, such as one they are developing to test athletes for doping.

Mariaelena Pierobon, 29, used the Virginia lab’s advanced tools to analyze pieces of tumor from the 51 Italian patients’ colons and livers. It would have been tougher for the researchers to acquire a similar set of matched samples in the United States, because of stricter rules at some of the review boards that govern such work, Petricoin said.

As a surgical resident in Padua, Pierobon saw the disease winning too often. “It’s difficult to get through it. You exactly know, when you see a patient, what’s going to happen to them,” Pierobon said. So she moved to research, and to Manassas. “I thought it was one way to do something for them.”

The key question was whether the highlighted routes driving the patients’ cancer were different in the colon and in the liver. That’s important because liver metastases are what can kill patients, but chemotherapy choices often have been based on the properties of the primary tumor in the colon.

The Italian samples were conclusive. “It was like, ‘Yeah, there’s a difference,’ ” Petricoin said. “It’s growing in completely different soil,” Liotta said.

Now they are using the new routes to find treatments. Which is where Kirsten Edmiston, the medical director of the cancer program at Inova Fairfax, and a colleague, Alex Spira, come in. “We are the next iteration,” Edmiston said.

In the clinical trial they are developing, which if approved could begin later this year, patients would come to Inova to get special liver biopsies. Pieces of their tumors would be tested at George Mason to see what works on them.

“That’s the whole point. [We] are becoming much more sophisticated in our ability to diagnose and really characterize the tumor and tailor the therapies based on the profile,” Edmiston said.

Then, she said, “you follow the clinical patient to see if the tumor gets smaller.”

A Creative Collaboration for Cancer Research (Video Clip)