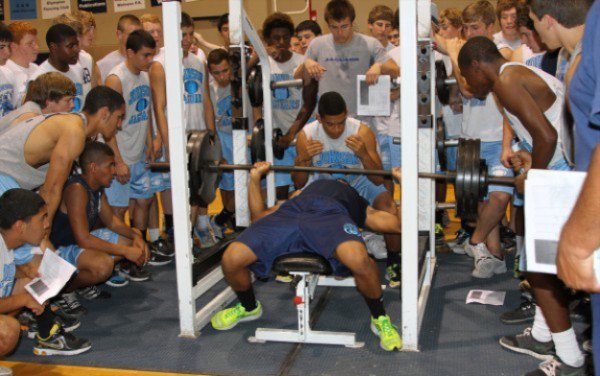

Walk into most high school (or college) weight rooms during the just about any sport team’s training session and a plethora of sounds attacks your ears. They typically include, but are not limited to:

- Grunting

- Gasping.

- Loading and unloading of plates.

- Shouting. (usually “UP! UP! UP! at an athlete who has horrendous form and too much weight on the bar)

- The inevitable clatter and crash of weights falling (usually by the same athlete who was the object of the yelling).

Ah, the sounds of a Burn Out.

For those of you who don’t know what a Burn Out is, allow me to explain. We’ll use a pretty typical example: the bench press. The bar is loaded with five ten pound plates (give or take a plate) on each side. The athlete bangs out as many reps as possible with that weight until failure. Then, a plate is stripped off each side and the reps-unto-failure is repeated. This goes on until the athlete is struggling, shaking, and gasping for breath as he pries the unloaded bar off of his chest in an attempt at one more rep.

For another example- one that might not be considered an official Burn Out- let’s take a volleyball team’s conditioning practice. The ladies are told to perform “suicides” for multiple bouts. Then, because their legs weren’t already fatigued from those and practice, walking lunges up and down the court. Knees are falling into valgus (inwards) with ACL’s straining to keep the knee joints intact; hips are wobbling back and forth and sacroilliac joints (the middle of the lower back) are screaming because of it (the girls are usually so fatigued by this point that their stabilizing muscles have all but conked out and now the ligaments are holding everything together). At the end they all collapse in a sweaty heap near the water bottles.

Logically, does this sound like a good idea? Before you decide, here are some objective points to think about:

- No matter who is doing a “burn out”, an experienced lifter or a younger lifter (which most of these high school athletes are the latter), their form is going to break down horribly by the second or third “burn out” set. When form degrades, so do joints and ligaments. Isn’t one of the goals of weight training to PREVENT injuries?

- Not only is form degradation a land mine of ligamental explosion, but it also teaches the athletes’ bodies to continue to perform with poor form.

Practice doesn’t make perfect, it makes permanent.

My shoes are older than most high schoolers.

My shoes are older than most high schoolers.It’s imperative the inexperienced lifters (such as every high school athlete. I don’t care how long they’ve been “lifting,” they don’t qualify as “experienced” if they haven’t even been alive longer than my Chuck Taylors) learn and practice safe and proper biomechanics for lifts, especially compound lifts such as the bench press, squat, and deadlift. They won’t be able to safely handle heavier loads (which is, by the way how one develops strength) because at some point in the future, something is going to give and it ain’t gonna be that barbell. Teaching kids to bang out reps willy nilly is setting them up for a long (or short) life of frustration and injuries in the weight room.

- Consistently training for failure, especially in new lifters, fries the nervous system. It’s really taxing and I don’t think most coaches or athletes understand the impact these burn outs have on their athletic performance. See, the nervous system is kinda important, it drives ALL muscular movement. For example, the faster the brain can send a signal to the muscles to contract, the faster the reaction time, or sprint speed, or the more explosive the tackle will be. Having a fresh, charged up nervous system means faster, stronger, and better players. Grinding out reps hinders recovery, which will negatively impact performance both on the field and in the weight room; again that opens the door for potential injuries (and losing games). The goal of a weight training session for athletes should be to recharge and energize them and let them walk out the door with some gas left in the tank. It shouldn’t be to run them into the ground and let them limp out of the door in an exhausted puddle of teenager.

- If the goal is to move fast, then you have to train fast. If a volleyball player needs to be explosive and quick on the court, how is training dozens of reps at a snail’s pace going to help? The body is remarkable and adapts to imposed demands (SAID principle). Simply, if you train the body to be slow, it’s going to be slow. Again, isn’t that the OPPOSITE of what weight training is supposed to do?

There are more reasons, but for now, swish these around in your brain and let them marinate a bit…

Now, back to the original question: does this seem like a good idea to practice with young, inexperienced, competitive athletes, male or female? (who, to be quite frank, need to be slowed down and taught proper form).

If we’re focused on strength, training sessions should include:

- 1 compound lift, executed with solid technique at an appreciable load for 3-4 sets of 3-5.

- 3-4 accessory lifts that are both somewhat sports-specific and balance out some of the inherent assymetries of volleyball players.

- Tight control on the overall load and volume (especially for in-season athletes) so as not to hinder recovery or overload their systems. This is a SUPER important point.

- If time, some soft tissue work and some correctives to help prevent overuse injuries.

By managing to load and volume or each work out, the coaches can help their players recover (thus grow stronger and faster) as well as boost their confidence by setting them up for success instead of failure.